Thousands of entrepreneurs gathered near Washington this week for an annual government conference. On the agenda: unusual solutions to major clean-energy problems.

Off the coast of California, the idea is that someday tiny robotsubmarines will drag kelp deep into the ocean at night, to soak up nutrients, then bring the plants back to the surface during the day, to bask in the sunlight.

The goal of this offbeat project? To see if it’s possible to farm vast quantities of seaweed in the open ocean for a new type of carbon-neutral biofuel that might one day power trucks and airplanes. Unlike the corn- and soy-based biofuels used today, kelp-based fuels would not require valuable cropland.

Of course, there are still some kinks to work out. “We first need to show that the kelp doesn’t die when we take it up and down,” said Cindy Wilcox, a co-founder of Marine BioEnergy Inc., which is doing early testing this summer.

Ms. Wilcox’s venture is one of hundreds of long shots being funded by the federal government’s Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy. Created a decade ago, ARPA-E now spends $300 million a year nurturing untested technologies that have the potential — however remote — of solving some of the world’s biggest energy problems, including climate change.

This week at a convention center near Washington, thousands of inventors and entrepreneurs gathered at the annual ARPA-E conference to discuss the obstacles to a cleaner energy future. Researchers funded by the agency also showed off their ideas, which ranged from the merely creative (a system to recycle waste heat in Navy ships) to the utterly wild (concepts for small fusion reactors).

Consider, for instance, wind power. In recent years, private companies have been aiming to build ever-larger turbines offshoreto try to catch the steadier winds that blow higher in the atmosphere and produce electricity at lower cost. One challenge is to design blades as long as football fields that will not buckle under the strain.

At the conference, one team funded by ARPA-E showed off a new design for a blade, inspired by the leaves of palm trees, that can sway with the wind to minimize stress. The group will test a prototype this summer at the Department of Energy’s wind-testing center in Colorado, and ARPA-E has connected the team with private companies such as Siemens and the turbine manufacturer Vestas that can critique their work.

While there are no guarantees, the researchers aim to design a 50-megawatt turbine taller than the Eiffel Tower with 650-foot blades, which would be twice as large as the most monstrous turbines today. Such technology, they claim, could reduce the cost of offshore wind power by 50 percent.

Or take energy storage — which could enable greater use of wind and solar power. As renewable energy becomes more widespread, utilities will have to grapple with the fact that their energy production can fluctuate significantly on a daily or even monthly basis. In theory, batteries or other energy storage techniques could allow grid operators to soak up excess wind energy during breezy periods for use during calmer spells. But the current generation of lithium-ion batteries may prove too expensive for large-scale seasonal storage.

It’s still not clear what set of technologies could help crack this storage problem. But the agency is placing bets on everything from novel battery chemistries to catalysts that could convert excess wind energy into ammonia, which could then be used in fertilizer or be used as a fuel source itself.

At the summit, Michael Campos, an ARPA-E fellow, also discussed the possibility of using millions of old oil and gas wells around the Midwest for energy storage. One idea would use surplus electricity to pump pressurized air into the wells. Later, when extra power was needed, the compressed gas could drive turbines, generating electricity. A few facilities like this already exist, though they typically rely on salt caverns. Using already-drilled wells could conceivably reduce costs further.

“This is a very early stage idea,” Dr. Campos told the audience. “I’d love to hear from you if you have ideas for making this work — or even if you think it won’t work.”

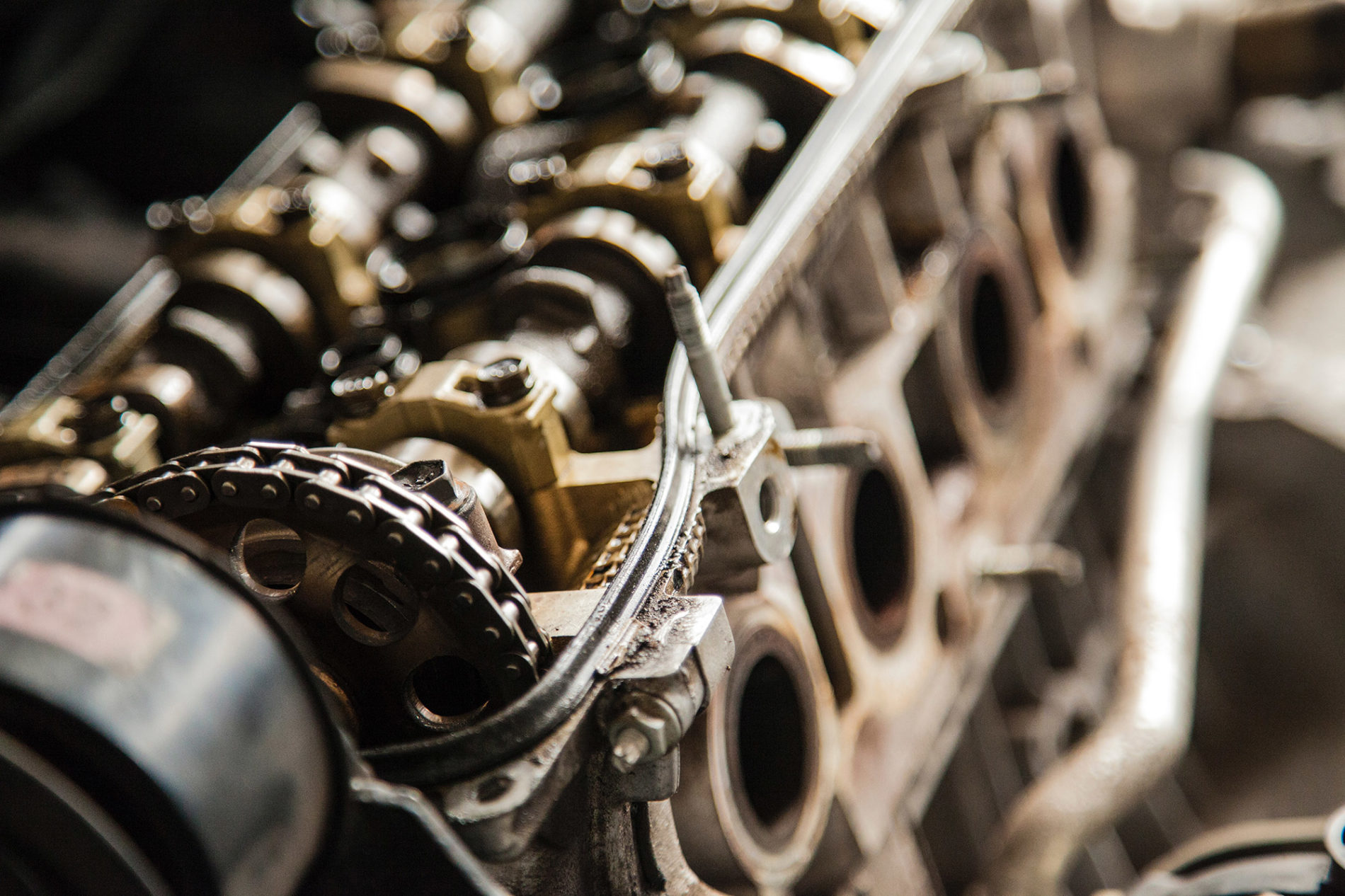

Other projects focused on less-heralded problems. A company called Achates Power showed off a prototype of a pickup truck with a variation on the internal combustion engine that it hoped could help heavy-duty trucks get up to 37 miles to the gallon — no small thing in a world in which S.U.V. sales are booming. Several other ventures were tinkering with lasers and drones to detect methane leaks from natural gas pipelines more quickly. Methane is a far more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

Looming over the conference, however, was the murky future of the agency itself. The Trump administration, which favors more traditional sources of energy such as coal, has proposed eliminating the agency’s budget altogether, arguing that “the private sector is better positioned to advance disruptive energy research.”

So far, Congress has rejected these budget cuts and continues to fund the agency. But the uncertainty echoed throughout the conference, even as Rick Perry, the energy secretary, sent along an upbeat video message lauding the agency’s work — a message seemingly at odds with the White House’s budget.

“We are at a crossroads,” Chris Fall, the agency’s principal deputy director, told the attendees. “But until we’re told to do something different, we need to keep thinking about the future.”

When Congress first authorized ARPA-E in 2007, the idea was that private firms often lack the patience to invest in risky energy technologies that may take years to pay off. Many solar firms, for instance, are more focused on installing today’s silicon photovoltaic panels than on looking for novel materials that might improve the efficiency of solar cells a decade from now.

Because energy technologies can take years to reach fruition, the agency does not yet have any wild success stories to brag about. By contrast, a similar program at the Pentagon created in the 1950s, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, can fairly claim to have laid the groundwork for the internet.

Instead, ARPA-E’s defenders have to cite drier metrics, like the fact that 13 percent of projects have resulted in patents, or that its awardees have received $2.6 billion in subsequent private funding.

In a review last year, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine concluded that “ARPA-E has made significant contributions to energy R&D that likely would not take place absent the agency’s activities.” The report added, “It is often impossible to gauge what will prove to be transformational.”

Originally posted by Brad Plumer on The New York Times (March 16, 2018) (View Original Article)